Introduction

The reason for this research project is that I was interested in looking at, does sculpture make children feel more confident and want to engage in art?

This is an area of personal interest for me as whilst at school I never felt particularly confident in art but I did enjoy working in three dimensions (3D). Although I enjoyed working in 3D there was little opportunity for this in my primary education, this is because I believe that teachers lack in expertise for creating sculpture (Edwards, 2013, p.191) and so has become a neglected area of the curriculum.

As a teacher I wanted to look at how sculpture could help children who do not enjoy art and perhaps do not like working in two dimensions (2D) but could benefit from working and constructing in 3D (Edwards, 2013, p.197), as this is a very different process to working in 2D.

Literature review

Sculpture is an important part of children’s art education, sculpture allows children to develop an understanding of texture, form, shape, space and balance in their art work (Coppock, 2004, p.4). This being because all these visual elements must be considered when making a sculpture as it is a physical object that casts shadows, is viewable from multiple angles and so these things must be considered. Sculpture can also be used as a way into mark making and using line (Edwards, 2013, p.194), because when making sculptures marks can be made into materials such as clay and use of straight lines when making armatures (Edwards, 2013, p.194).

Sculpture allows children to experience the world around them (Cox and Watts, 2007, p.57), thinking about structures they see and experience. This is because children are constantly

surrounded by sculpture in their everyday lives (Utley and Madson, 1997, p.9). Examples could be ceramics work, work with clay or even household ornaments (Cox and Watts, 2011, p.57).

Children have an enthusiastic and excitement for working in 3D (Clough, 1996, p.7) as children enjoy the construction process of making sculptures (Fawcett and Hay, 2004, p.239). Sculpture is an exciting experience that engages children and offers a unique creative process (Edwards, 2013, p.208) which cannot be achieved with other art forms due to the elements of construction that are involved. Sculpture allows children to explore their creativity as they are not limited by working in 2D and are able to explore their artistic practice through their ideas, feelings and own imagination (Cox and Watts, 2007, p.55).

Sculpture allows children to gain an added understanding of their own work and the work of others, as they are able to view sculptures from multiple viewpoints (Barnes, 2002, p.172). Children are also able to explore their own art work, through touch as well as interacting with shadows cast by the sculpture, adding to the overall impact of the piece of work as well as the weight and features of what they have created being a physical object (Barnes, 2002, p.172).

In teaching sculpture, teachers lack the confidence and knowledge to teach high quality sculpture lessons (Manners, 1995, p.12) and so children unfortunately often do not get to experience sculptural work. Much of the work children take part in during the primary years is often 2D (Clouch, 1998, p.9) meaning children do not get to experience, until they start secondary education, specialist sculpture lessons. It could be argued that due to this children’s art education is lacking in the primary years, in the art national curriculum it states that, children should master a range of techniques, sculpture being one of these (Department for Education, 2013, p. 177). Children may also not get to experience sculpture due to a lack of funding of the arts in primary school (Cox and Watts, 2007, p.57). Although sculpture can be resourced cheaply through use of common household materials such as cardboard boxes and cardboard tubes (Fawcett and Hay, 2004, p.238), schools with their limited budgets cannot afford to buy specialist materials for sculpture (Cox and Watts, 2007, p.57). If teachers are not confident in teaching sculpture, art coordinators with their limited budgets are not likely to purchase specialist materials.

It is important to actively engage children in art (Green and Mitchell, 1997), sculpture is a means of achieving this, its elements of construction, design and thinking in 3D creates a unique visual of art work unachievable with 2D work (Cox and Watts, 2007). In light of this review of literature my research question was, does sculpture increase children’s confidence and engagement in art?

Methodology and methods

The aims of my research were to look at if there was a difference in children’s engagement and confidence in art after taking part in high-quality learning, experiencing new skills and making of sculpture. Whilst carrying out my research I used a qualitative and quantitative approach, conducting an experiment looking at two groups of children.

All children had the opportunity to attend the art residential. However, a small group of children did not want to attend. These children made up control group and so did not take part in the sculpture workshop. The other group, were my experiment group and had choose to attend the residential, taking part in four sculpture workshops throughout the week.

I collected quantitative data using two questionnaires looking at children’s confidence in art. The two questionnaires had slight variations addressing whether the children had attended the sculpture workshops, or taken part in activities in school. These were based on emotions, with my questionnaires looking at how their confidence in art may have changed after this week. This was measured using a 1 to 5 Likert scale, as well as asking questions that required children to give closed yes or no answers and open ended questions that were looking for a personal response from the children (Robert- Holmes, 2011, p.172), about their own sculpture education and opinions of taking part in sculpture workshops in the classroom. Please refer to appendix 1 and 2 as examples of questionnaires used in my research.

I analysed the quantitative data gathered by using pie charts to show the percentage of children in each group’s confidence. I decided to use a pie chart as my control group sample size of 9 was significantly smaller than my experiment group with a sample size of 29. For this reason I decided to use pie charts to interpret the results of the Likert scale question to show a comparison of percentages rather than the number of children who answered in each group as this is the fairest way of making a direct comparison. I also used this method to show my results for my yes no closed questions.

I gathered my qualitative data through assessing a sample of the children’s sketch books from my control and experiment group. I chose my sample size using a stratified sampling method to show a true representation of my results, as this means that the number chosen from each of my groups was proportional to the size of the group as my overall population was 38 children. I wanted a sample size of 9 students from my population of 38 students, my calculations were as follows:

(29 ÷ 38) x 9 = 6.9 children from my experiment group rounded up to 7 children.

(9 ÷ 38) x 9 = 2.1 children from my control group rounded down to 2 children.

I then used a simple random sampling method to select the children whose sketch books I would be looking at to represent my samples from each group without bias. Every member of the population in each group was given a number starting with 1 and using the #Ran key on a scientific calculator to generate random numbers to select the sample children.

I examined the qualitative data by using the children’s sketch books to see if they supported the findings of my questionnaire, as well to assess the effectiveness of the sculpture workshop or lack of workshop on the children’s confidence and ability in art. I looked at the progress in the children’s sketch books before and after. I assessed the children’s work looking at the children’s engagement with the lesson (Eisner, 2002, p.180) and how they had produced the work in their sketch books in response to the learning objectives for the different session. I was not looking for an amazing piece in terms of outcome but in how they had shown engagement and confidence in the methods of art they were using.

During my investigation I encountered no problems in gathering my data. Before completing my research in school I submitted an ethics protocol to my dissertation supervisor, as well as gaining the permission of the headteacher and deputy head to complete research in my placement school, collecting photos, using questionnaires and looking at children’s sketch books.

Findings

My first set of results looked at children’s confidence in art, which I have measured by looking at how confident the children felt about the subject of art to compare the differences between my control and experiment group.

Looking at the results presented in the pie charts above it can clearly be seen that 76% of children felt confident or very confident in my experiment group, meaning only 24% of children felt either unconfident or no change. Whereas the control group had a bigger percentage of children not feeling confident in art or unchanged at 89% with a bigger range of results compared to the experiment group. This shows that the engagement of the children in the experiment group was greater than that of the children in the control group.

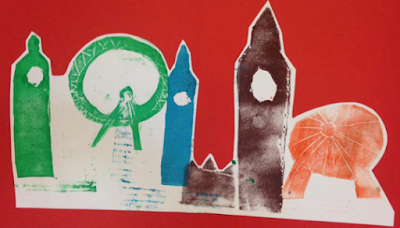

After examining and assessing the children’s work in their sketchbooks, looking at work before and after the sculpture workshops or lack of workshops, there is an improvement in the children’s work who had attended the workshops.

When looking at samples from the sketchbooks of the children from the control group there is no significant improvement in the work shown. Although child 2 has produced a good piece of work before the week in which the sculpture work was held, their work after shows no improvement of skill, and in terms of development in sketching their does not appear to be improvement in outcome of work.

The images of the children’s work from my experiment group show increased confidence in their work, in the way in which they are using the art materials and improved technique in their work. I saw an improvement not just in the children’s technique but also in their competence in drawing. Even child 18 who had not made noticeable improvement in their drawing ability had however made noticeable improvement in their skill of using the resources. It can clearly be seen that they have attempted to use a range of tone rather than just one tone that they had in the previous piece of work.

I also wanted to know if the children had taken part in any sculpture activities before or if this was the first time for my experiment group, if they had taken part in a sculpture work shop.

I also wanted to find out if my control group had had any experience of sculpture to support my findings about how sculpture can support children’s learning in art. The results are as follows:

In the experiment group 59 % of children had not taken part in a sculpture lesson previously and in the control group 67% of children had not previously taken part in a sculpture workshop in school. This further supports my findings from my Likert scale question assessing children’s confidence in art.

The data that I collected also looked at finding out how sculpture could improve or not improve children’s engagement in art. The children had a positive attitude to art and were engaged with the task of sculpture. When the experiment group were asked if they wanted to do more sculpture work in school, 97% of children said yes that they wanted to take part and a 100% of children in the control group also stated that they would like to take part in sculpture work in school.

This supports the idea that sculpture can increase children’s engagement in the arts because with the exception of 3% of children, however this only represents one child. All other children in both groups would like to see more sculpture in the primary national curriculum.

The children were also given the opportunity to express why they wanted to do more sculpture work in school in an open question format where I wanted the children to give their own personal reasons. In the children’s own words some of the responses to the question of why would you like to do more sculpture in school are as follows:

Participant 5

"I would like to do more of this in school, it is really fun because it is using my hands2.

Participant 14

"Because all activities were hands on".

The children liked that sculpture involved using their hands to construct the sculptures, as this is a unique style of working when creating sculpture to any other art form. The children also spoke about working in a different dimension as a reason for wanting to do more sculpture:

Participant 22

"Yes because I like looking at 3-d stuff".

The children also spoke about sculpture being a new experience for them as a reason for wanting to do more of this medium of work in school:

Participant 1

"They are very awesome, I don't usually do stuff like that".

For some children it was the process which was important to them and the reason for their engagement and wanting to do more sculpture work in school:

Participant 8

"I enjoyed putting the modroc on the paper sculpture".

Participant 9

"I liked getting messy and mucky. I found out that Barbara Hepworth made her sculptures in a similar way".

Having looked at the children’s responses I have examined the questionnaires for both of my groups and collated the data that I have found and

categorised their answers into four areas using a pie chart. The pie chart shows the children’s reasons for the whole population of the children in both my experiment and control group. The results are:

This pie chart supports the idea that sculpture engages the children in art as the children were able to give reasons for this. 70% of children expressed that sculpture was a new experience that they enjoyed doing. If children are to be engaged with an activity it is important the activity they are taking part in they find enjoyable and so this supports my findings that sculpture increases engagement in art.

Discussion

From my findings I found that the children who took part in the sculpture work shop saw an increase in confidence towards art. The majority of children in both groups had not previously taken part in any sculpture activity and so it can be suggested that the results in which children gave when answering how confident they felt about art is as a result of taking part or not taking part in the sculpture workshops. Confidence in art can therefore be linked to children having experience of sculpture in their art education. This may be because sculpture can be linked to an increase of confidence as it draws on many skills (Palmer, 2008, p.2) that children do not have the opportunity to use during art lessons that look at other areas of the art curriculum such as drawing or painting.

For the children who were a part of the experiment group, their before and after work showed an increased understanding of form and texture, being able to use materials to communicate ideas (Palmer, 2008, p.2). The children showed more skill in their use of tone in their work, whereas the children in the control group showed no significant improvement in the skill of their work. Their work is flat with no varied tone, showing no improvement between their before and after work.

In figure 1 the children can be seen constructing their armatures for their sculpture by creating in 3D seeing how light falls and creates light, dark and shadows. This enabled a greater understanding for the children who were in the experiment group whilst drawing, considering these elements in their work. This found confidence in art to be able to use these skills is explained by Barbara Hepworth in her own words in the documentary The art of Barbara Hepworth (2003) ‘I the sculpture am the landscape, I am the form and I am the hollow the thrust and the contour’. She talks about how sculpture unlike any other medium is a personal experience that sees the children interact with their work feeling what they are creating. This interaction with the work therefore creates a confidence in the children’s ability but also in their engagement.

My findings also revealed an increase in engagement in the children that had been a part of the experiment group. Having taken part in the sculpture workshop the deduction can be made that the 97% of children in the experiment group said that they wanted to take part in more sculpture because they enjoyed the workshop they had the opportunity to be a part of whilst on residential. This is because sculpture is an exciting and engaging area of the art national curriculum (Boys and Spink, 2008, p.22). Furthermore, it could be suggested that the children in the control group, 100% of them, wanted to take part in sculpture work in school. This could be because these children had seen the experience that the experiment group had had and seen the sculptures that they had made. Seeing the work of others was inspiring for the children and could have been the reason for them wanting to do sculpture (OFSTED, 2009, p.19).

Figure 2 shows the children creating the armatures for their work and figure 3 shows the experiment group applying the modroc to their sculpture. In the picture it can be seen that all the children are engaged with the task of applying the modroc. This was a new experience for the children and as suggested by Clough (2000, p.9) is important for children to be able to experience using sculpture materials. The children all look to be engaged and involved in the task, this is because sculpture is a personal and social experience (Robinson, 1989, p.29). The activity lends itself to working with others and in the pictures children are working alongside each other experiencing this new opportunity. Working with sculpture encourages curiosity which engages children when they have the opportunity to use new materials (Manners, 1995, p.14). Again this is further supported by the quote from my findings that made a direct reference to the enjoyment of applying the modroc, this being because it was a new experience as well as a social one.

When asked if the children would want to take part in more sculpture work all children in both groups said yes with the exception of one child. I think this is because sculpture actively engaged children who do not enjoy taking part in the typical art that children are exposed to in primary school, this being painting and drawing (Edwards, 2013, p.208). This shows that sculpture engages children in art, and engagement is key to involving children in art and making them open to trying new things (QCA, 2004, p.9). This highlights why sculpture is needed in the art curriculum and it is important to ensure children all have access to high quality sculpture education throughout primary school.

Conclusion

The main findings from my research were that sculpture can result in children feeling more confident and engaged in art education. This is a result of children working with their hands, as explained by the children, using materials and working in different scales (Edwards, 2013, p.204). Sculpture engages children due to children feeling a sense of achievement and self-confidence (QCA, 2004, p.9). Sculpture lends itself to children achieving in art due to children being able to use their hands and making art in 3D. It is a different experience and allows children the opportunity to make a lasting artefact (Cox and Watts, 2007, p.57). Outstanding art education ensures that children experience new skills (OFSTED, 2009, p.51) which is why sculpture can increase confidence and engagement. The children in the experiment group were engaged with the activity as it was a new experience, having the opportunity to produce a sculpture of high quality using sculpture techniques, resulted in the children feeling more confident after the workshop.

What I have found out from my research fits with the literature about art education and sculpture in general. Literature suggests that sculpture is a ‘wide field of experience’ (The art of Barbara Hepworth, artists own words, 2003,) and that art that is created through interaction with materials is important for personal growth, fundamental to all art education (Fleming, 2012, p.71).

Sculpture is an experience ‘it is something you experience through your senses’ (The art of Barbara Hepworth, artists own words, 2003, 45.13 min) which has been demonstrated in my research as confidence and engagement in the subject of sculpture.

My findings do not however build upon existing specific literature regarding sculpture education. This being because there is very limited literature on specific sculpture education, and I was unable to find any journal articles that looked at sculpture education and the benefits it could provide to children. The only work that I was able to find on sculpture education were books that looked at all the different aspects of art education such as Bowden, Edwards and Cox and Watts. The only work that I could find specifically looking at sculptures and materials used for 3D work were by Clough, Coppock, Manners, Utley and Magson. These works were simply a how to guide and made little reference to the benefits the children could take from working in 3D as well as being unreferenced and supported by other literature themselves. This lack of literature is why I believe research into sculpture education is needed, to look at benefits of this style of work and why it is not happening in schools to be able to make changes to ensure all children have access to education that engages, inspires and challenges them (Department of Education, 2013, p.182). Children who find other subjects difficult may excel in 3D work as it is a different way of working and so

develops children’s confidence in their ability in art (Coppock, 2004, p.4). It has been proven through the research I have completed that sculpture education can achieve this.

The direction in which I would take my research next would be to look at teachers’ confidence in teaching sculpture. Teachers, although aware of the benefits of sculpture education, can be put off trying this in class as they believe it is beyond them in difficulty level (Bowden et al, 2013, p.68). Some teachers do not identify themselves as artistic (Alter et al, 2009, p.22) which is why I want to continue this study by looking at if the same ideas of holding workshops can increase teachers’ confidence and engagement through effective continual professional development. The findings of this study show sculpture can increase engagement and confidence, if teachers do not feel confident to teach sculpture then children will not get this experience of art and will not be receiving a broad and balanced curriculum (Bowden et al, 2013, p.69).

In my future practice this research has shown me how important it is to make sure children have opportunities to make sculptures throughout their primary education. However, staff are reluctant to take a risk in teaching sculpture as they are afraid of what might go wrong (Bowden et al, 2013, p.67). In my future practice I will work to develop confidence and improve teaching in sculpture work (Burton, and Brundrett, 2005, p.142). I will look to do this through promoting sculpture education and its benefits in my own classroom by displaying 3D work that I have made with the children (Bowden et al, 2013, p.69). As well as organise professional development for teaching staff (Fawcett and Hay, 2004, p.237) highlighting the importance of sculpture as well as giving examples and ideas as to how to do sculpture easily in school.

The only issue with my research was the sample size for each group was different, the control had only 9 children whereas my experiment group had a sample size of 29, meaning the numbers were significantly different. This was due to the numbers of children that attended the art residential trip. If I were to redo this experiment I would want to ensure that my sample sizes were both equal and of a larger size, therefore improving the validity of my results (Robert- Holmes, 2011, p.70).

Reference List

Alter, F., Hays, T. and O’Hara, R. (2009) ‘The challenges of implementing primary arts education: What our teachers say’

Australian journal of early childhood. 34(4), pp.22-30.

Barnes, R. (2002)

Teaching Art to Young Children 4-9. London: Routledge.

Bowden, J., Ogier, S. and Gregory, P. (2013) A

rt and Design Primary Coordinator’s Handbook. London: Collins.

Boys, R. and Spink, E. (2008)

Primary curriculum teaching the foundation subjects. London: Continuum.

Burton, N. and Brundrett, M. (2005)

Leading the curriculum in the primary school. London: Paul Chapman Publishing.

Clough, P. (1996)

Clay in the primary school. London: A & C Black.

Clough, P. (1998)

Sculpture materials in the classroom. London: A & C Black.

Coppock, L. (2004)

Outstanding art imaginative three dimensional art and sculpture. 2nd edn. Dunstable: Belair.

Cox, S. and Watts, R. (2011)

Teaching Art and Design 3-11. London: Continuum.

Department for Education (2013) T

he 2014 primary national curriculum in England key stages 1 and 2 framework. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-primary-curriculum (Accessed: 25/04/2015).

Edwards, J. (2013)

Teaching Primary Art. London: Pearson

Eisner, E.W. (2002)

The arts and the creation of mind. New Haven and London: Yale university press.

Fawcett, M. and Hay, P. (2004) ‘5x5x5 = Creativity in the Early Years’

Primary Art Education, 23(3), pp. 231-246.

Fleming, M. (2012)

The arts in education an introduction to aesthetics, theory and pedagogy. London and New York: Routledge.

Green and Mitchell (1997)

Art 7-11 developing primary teaching skills. London: Routledge.

Manners, N. (1995)

Three- dimensional experience. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

OFSTED (2009)

Drawing together: art, craft and design in schools 2005/08. Available at: http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/10624/1/Drawing%20together.pdf (Accessed: 27.04.15).

Palmer, C. (2008)

The coast, Boats and Rigging KS2 SOW. Devon: KCC Art Department.

QCA (2004)

Creativity: find it, promote it. London: QCA Publications.

Robert- Holmes, G. (2011)

Doing your early years research project a step by step guide. 2nd edn. London: Sage.

Robinson, K. (1989)

The arts in schools principles, practice and provision. London: Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

The Art of Barbara Hepworth (2003) Recorded by Gina McKee [DVD]. England: Illuminations Productions.

Utley, C. and Magson, M. (1997)

Exploring clay with children. London: A & C Black.